Nov 21, 2017 | Events, Roundtables

Speaker: Kevin Thomas, Director of IPInitiatives

The session opened with Kevin making the statement that the UK construction industry is capable of achieving great things, but tends to be successful despite the process, rather than because of it. change gets more expensive as the design of the project progresses from design to delivery, often because there is a lack of ownership of the overall outcome. The IPI model recognises combines the two processes so that the client designers and the delivery supply chain all combine to work as a single team under an ‘alliance’ agreement.

The key features of the arrangement include

- Common selection process (OJEU) based on ability to achieve.

- New Alliance Contract creates a virtual business ‐ a Board of partners with ‘skin in the game’.

- The whole team optimise performance deciding who does what, when and how.

- Open book – pay for people and buy things separately – through a Project Bank Account.

- Work top-down from a benchmarked investment target to meet the needs.

- Supply chain is involved in all design decisions.

- Savings are achieved by stripping out processes, products and procedural waste & inefficiency.

- The team identify opportunities and risks ‐ allocating them to the party best suited.

One of the key features of the arrangement is that all of the usual insurances taken out by the different parties to a construction contract are wrapped together, to provide the client with protection against a cost overrun.

New mindset required

The process requires a significant shift in mindset by all of the participants. There are many different features to the IPI process, but one of the biggest changes is that there is no one to blame under a contract, because everyone is tied together. The process works through the following steps:

Step 1 – Establish the Need. The problem to be solved and the funding level anticipated

Step 2 ‐ Form an Advisory Team. Establish the strategic brief & success criteria, validate the investment target and select the team

Step 3 ‐ Establish the Alliance. Client and key partners bound together through an alliance contract and gain/pain share incentives who confirm the functional requirements, propose the solution and confirm the target cost

Step 4 ‐ Approval to Implement. Client & underwriter approval to develop and deliver the solution and incept the IPI policy to cover the agreed target cost

Step 5 – Implementation. Open book collaborative design, development and delivery

Step 6 – Transition to Defects Liability. Completion and proving, 12 months of soft landings and seasonal commissioning and 12 years of defect liability

Case Study – Dudley Advance II.

The IPI model has had a long gestation period, being first conceived in 2003. It has finally been tested on a live project for Dudley College. This is a higher education facility comprising five floors of lab/teaching space and a large open hanger-like space for large-scale projects. The building is stacked with innovation, and built to a high finish.

The project began in 2014 and was delivered to the client on the program for the start of the educational term and within the original cost parameters. Given the challenges that the team faced over the delivery period, it is likely that the building would have faced significant delays and would have incurred significant cost overruns, had it been built using traditional design and procurement methods.

Kevin provided the audience with a frank summary of the learning from the project. Some of the things they expected to happen include:

- A true no-blame culture would emerge

- A “best for project” focus would be adopted for solution development and problem-solving

- Supply Chain would engage, lending expertise so design happened only once

- The team would run the project on Opportunities and Risks

- The Alliance Board would function as a business board

- BIM would create better efficiency, give asset management solutions

- New processes and procedures would be created

- Behaviours would change

Some of the things that were unexpected included:

- Working within the investment target is not a core skill for many people in the industry.

- The level of facilitation, coaching and mentoring was much higher than anticipated.

- It initially took a lot of effort to get people to take leadership.

- How much support some businesses would need to adopt BIM

- Impact of adopting BIM guidance

- Limitations of the ‘normal’ programming processes

- Cost of and time to achieve policy inception

- Difficulty integrating design, delivery & commissioning activities

- The extra benefits of 4D

Summary

Having been aware for some time that the IPI pilot was running, the ResoLex community were excited to see how it would turn out. The room was therefore delighted to hear of the IPInitiatives team’s experiences, and many were keen to see how the process might be used on their future projects. Kevin was keen to point out that the process is still in its early stages, and whilst there is another pilot currently underway, there is still a long way to go before the process becomes a mainstream alternative to the traditional procurement route.

One of my main takeaways from the evening was Kevin’s observation that once the collaborative mindset took hold, the energy and desire within the team to deliver was a joy to work with. Many words are written and spoken about the need for more collaboration in the construction industry. Kevin and his fellow directors have shown us how it can actually work in practice!

Oct 24, 2017 | Events, Roundtables

Speaker: David Hawkins, Operations Director and Knowledge Architect of ICW (Institute for Collaborative Working)

David began his presentation by comparing the contrasting perceptions of collaboration of synchronized swimming with sharks at one end and a team hug at the other. Neither is a true picture of what collaboration really means.

He explained that as business is shifting, old adversarial practices are proving inadequate to meet the challenges of organisations seeking to compete and survive in the 21st century.

In construction, whilst individuals often collaborate, organisations do not. There is too much reliance on informal relationships which disappear when the people move on. The aim of the standard is to establish formal structures so that the relationships are maintained irrespective of the people involved. The Standard gives companies a language and a platform upon which to develop a more effective way of working.

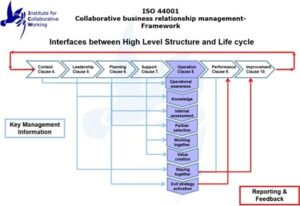

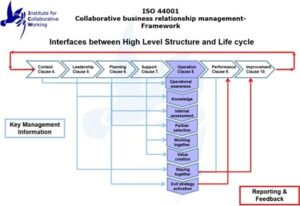

As can be seen from the slide deck, the standard is designed around a number of stages, each one asking the parties to think and plan how they will work together. The structure of the model is illustrated below.

Some of the useful insights from the presentation were as follows:

- That most organisations are inefficient and waste a great deal of inefficient

- There is and assumption that people will use their common sense – Voltaire commented back in 1694, ‘common sense is not so common’.

- Constructive conflict can drive innovation. This occurs when collaborative relationships are really working effectively.

- Universities are still teaching a 40 year old command and control model ill suited to the modern complex economy. A survey of project managers highlighted that the biggest challenges are with relationships. One of the real challenges is the lack of skills to implement the collaborative process.

- The Standard is not a set of proformas. The danger with such an approach that is the organizations mechanism not an external consultant.

- Risk – Observation that banks and insurance organisations are going to be much more concerned about relationships risk in the futures as they begin to understand the value created by effective partnerships.

- Contracts – tend to be written in anticipation of failure rather than seeking to drive the conditions for success. David expressed the view that NEC4 has missed the opportunity to push the industry to push the boundaries and encourage the client and the contractor to approach public projects in a different way.

David concluded the session by reiterating the point that the key to success is the belief of the senior leadership. He emphasized the point that simply having the certificate on the wall is largely a waste of energy. The objective must be to use the Standard to build a better business.

Sep 21, 2017 | Events, Roundtables

Speaker: Rob Horne, Previous Partner at Simmons and Simmons, Current Partner at Osborne Clarke

Rob opened the session by asking the audience to define collaboration and drew attention to the Latin origin of the word ‘collaboration’ which means to ‘work together’. The word has become increasingly used in the construction industry as a desirable objective without recognising the need to fundamentally change how to approach the procurement and delivery of a project. The point was emphasised using a quote from Dale Evans of the One Alliance for Anglia Water who stated in a recent interview in New Civil Engineer “At the moment there are too many examples of organisations asking people to collaborate, but then dropping them into a business model that is the same [traditional procurement model]”.

Collaboration can be seen to be an outcome that arises when all parties adopt the necessary behaviours. This requires a level of communication and comprehension skill that is difficult to articulate in a legal document. For example, phrases requiring the parties to work in a spirit of ‘mutual trust and cooperation’ (NEC 4, clause 10.2) or ‘trust, fairness and mutual cooperation’ (PPC 2000, clause 1.3) may set out the intention but are difficult to enforce.

Rob explained that a contract is essentially a mechanism to try and manage risk. If all goes well and the parties are all working towards the same goal, then the contract is rarely required once it has been signed. When projects do not go as planned, then the contract becomes the primary mechanism to agree on differences between the participants. A number of recent cases were used to illustrate the difficulty in applying the provisions around trust, cooperation and good faith. (see slides)

Rob’s purpose was to expose three myths around the concept of collaboration in construction contracts which can be summarised as follows

- Myth 1. A contract can be collaborative. Contracts and Collaboration are different. One is a set of rules the other is the application and implementation of those rules. A contract, of itself, is not collaborative, to be collaborative it would have to do something but contracts are inert and unmoving. Collaboration, of itself, is not creating or performing a contract.

- Myth 2. Collaboration is essential. There is a valid question as to whether the alternative approach of clarity and proper perpetration actually makes more of a difference. Collaboration is a “fashionable” approach to contracting. Take care in what it can actually achieve.

- Myth 3. Collaboration is incompatible with enforcing a contract. Collaboration has to work within a framework and that framework must be capable of enforcement. Enforcement does not have to be through a court or formal tribunal, it could rely on a core group for example under FAC-1 and PPC.

Rob summarised the presentation by pointing out that when genuine collaboration does occur, it happens because humans decide it is in their mutual interest to pursue a particular goal or objective. The role of the contract is then primarily to create a framework for this ‘magical’ process to happen.